Read good books.

Watch webinars offered by people you respect.

Listen to podcasts hosted by smart, generous people.

There are a lot of brilliant people out there giving away their

very best secrets, and you owe it to yourself – and your

business – to learn as much as you can from them.

I know the sheer volume of information out there can feel

overwhelming, but dedicating some time each day to learning

will pay off in a thousand different ways.

Consider seriously points of view you don’t agree with. What do

they know that you don’t?

I had to share this THRILLING email from one of the participants in the Start Right Where You Are course —-

“If you had been in the room yesterday when I went to the most unlikely place in the house and pulled out the jeweler’s pouch with the long-lost diamond earrings, you would have heard screams of joy and excitement that have never before come out of a classy 85-year old’s mouth!

[My friend] Gloria had asked me last Friday if I could “logically and systematically” go through all of her jewelry boxes, elegant purses and designer jackets to see if her lost earrings could be found.

I wrote the exercises from Start Right Where You Are Lesson #2 right before I went to her house.

After we had spent time checking the logical places diamond earrings could be lost, I remembered your definition of Intuition as Cognition without Knowing…no documented or logical evidence and I got inspired to follow my “gut.”

I walked to a very public place in her house and noticed a one-foot tall Chinese wedding basket and started to walk away because

“logically, who would hide very expensive, large and valuable diamond earrings in the middle of a well traveled area?”

Then I remembered your definition and went to the Chinese basket and opened the top and it looked empty, however, I followed my intuition and swept my hand around the dark circle of the basket and found a small jeweler’s leather bag and brought it to Gloria.

As she opened it and discovered her treasure she was ecstatic and said, “You’re a Genius! How did you know to look there?” and I shared my Sam Bennett homework with her and let her listen to part of your call to hear your strong belief in Intuition.

She was so happy, she gave me a brand new necklace that we had found from India when we were looking in the “logical” places earlier.

Today she called me from her new home in Rancho Mirage and said,

“I am telling everyone this story and I am going to follow Sam’s list and get rid of my “Intuition Killers!”

I felt so alive when it happened and wanted to let you know how powerful your work is to get us back in touch with our Being…..

Joyous in Long Beach,

Ashley Waugh, an even bigger fan

And when I asked Ashley if I could share her story with you, she graciously agreed and added —

“I would love to be a small part of anyone falling in love with their intuition again…..”

So…what can you do follow to YOUR intuition today?

Let me know — you know I love to hear from you.

You’re stuck because you think you know what you don’t know.

But you don’t.

Because you’ve never done This before.

You think you know how your project is going to unfold, and I’m here to tell you that you don’t.

You think you know how much people will pay for your product or service, and you don’t.

You think you know how much work your project will be for you, and you don’t.

You think you know how your project will be received, and you don’t.

All these things you think you know (but don’t) are keeping you from moving forward.

Think back to your own experience – every single project you have ever done for the first time has grown and stretched and changed and evolved as you’ve worked on it, right?

So let’s pretend you are an absolute beginner, and enter this project with a spirit of joyful exploration.

The Isle of Skye

What if there was

another you who lived on the Isle of Skye?

And what if, in the soft light of that

other home,

you forgot to think the thoughts

that hold you back?

What if, in the mist,

you knew all,

you forgave all,

and you remembered to be

oh so gentle with yourself?

What if you, on the Isle of Skye,

could just breathe,

wearing a warm sweater

and half a smile?

And what if your heart’s own work just flowed out of you –

lipping in between the endless hills and endless sea – a balm unto the world?

© 2014 Samantha Bennett

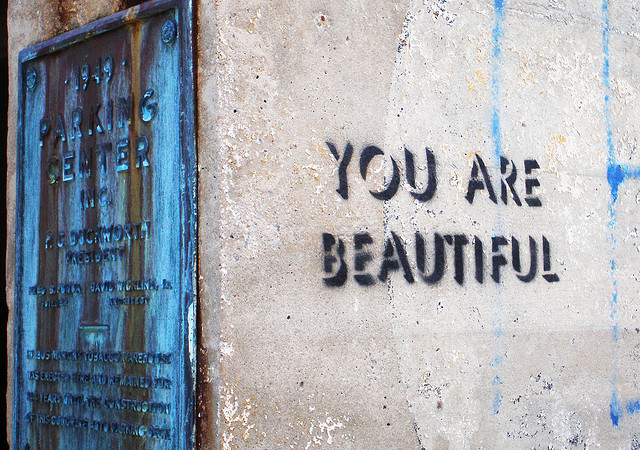

Guess what? It’s okay to have some positive thoughts about yourself.

Many of us were raised in intellectual households, where if you couldn’t prove your point, well, you were just being delusional. I’m asking you to be a little delusional. You may be reluctant to think nice thoughts about yourself. I understand. You may feel that your negative thoughts “keep you in line” and you don’t want to “get a big head.”

Darling, you will not get a big head. I promise.

EXERCISE: TEN NICE THINGS

Step 1. Write Down Ten Successes, Wins, or Blessings from the Past Year.

Grab a pen and write down ten good things that have happened in the past twelve months. It’s time to give those chattering critical voices in your head a rest. It’s time to change the tape. It’s time to accentuate the positive.

If it doesn’t work, no worries — you can always go back to thinking negatively any time you’d like.

(“I paid off all my credit cards” or “I learned how to cook a perfect roast chicken”), things that happened to you (“My cousin gave me that wonderful birthday present” or “I got asked to perform the solo”), things that happened around you (“There is some jasmine growing right next to my bedroom window, and it smells heavenly” or “Those noisy neighbors finally moved away”) or (most likely) some combination of the above.

Don’t have a contest with yourself about the “best” things that happened to you; just list some things that, when you reread the list, make you nod and smile to yourself and think, “Yep. That’s pretty good.”

Step 2. Write Down Ten Nice Things about Yourself.

Now make a list of ten nice things about you. They may be nice qualities that you were born with, like your quick mind and your lovely eyes. They may be nice skills you’ve learned, like your gorgeous gardening skills and your ability to run a mile without losing your breath.

Or maybe they’re things other people appreciate about you, like what a safe and courteous driver you are, and how you always remember everyone’s birthday. Push yourself to come up with ten.

After all, the assignment is not to write down ten extraordinary things about you, or ten things that no one else in the world has ever done — just ten nice things that, again, you can look at and say, “Yep. That’s pretty good.”

From now on, you must keep track of every single compliment you get.

The rule is this: only write down the phrase or adjective– don’t record who said it or why or what you think they meant.

And I do mean EVERY compliment.

Even the ones you don’t think matter, like, “Oh, you look nice today,” or the generic ones like “Good job,” or even the ones that you suspect aren’t really meant as a compliment, like, “You are so funny…”

If you get one of those, then you write down:

Looks Nice

Does A Good Job

Funny

OK?

After several months, review the list and see what there is to see.

Here’s one to start with:

I think you are good and brave.

(Now go write that down.)

—Sam